In “God is a Question, Not an Answer,” William Irwin explains his doubts about anyone who is certain that God exists or that God does not exist. “People who claim certainty about God worry me, both those who believe and those who don’t believe. They do not really listen to the other side of conversations, and they are too ready to impose their views on others. It is impossible to be certain about God.” It’s better to admit that we all live on a “continuum of doubt.”

Luck matters

Is success up to you, or does it just happen to you? In “Why Luck Matters More Than You Might Think,” Robert K. Frank says that luck plays a bigger part in success than most people think. And the more you appreciate the contribution of luck to your success, the happier and more generous you are likely to be.

Brain hacking

In “The Mind’s Biology,” Amy Ellis Nutt reports that some doctors are reaching past the symptoms of mental illness to identify and fix the brain circuits underlie the problems. One of those doctors is Hasan Asif. “Asif says that a person’s mental makeup is a kind of hierarchy, with personality on top, which is created by brain states that arise from circuits firing in a certain pattern below. With psychotherapy, you tweak the brain from the top down, dealing first with a patient’s personality and temperament. But with neurofeedback, combined with qEEG, he said, he tweaks his patients from the bottom up, identifying the brain areas involved and then retraining those circuits to fire differently, resulting in changed moods or mental outlooks.”

Improving morality through robots

In “Can we trust robots to make moral decisions?” Olivia Goldhill describes research by philosophers and computer scientists to program robots to make ethical decisions. One big reason for asking how to build an ethical machine is that “work on robotic ethics is advancing our own understanding of morality.”

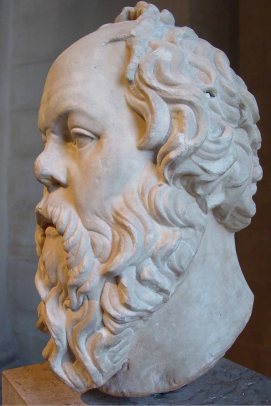

Socrates’ heirs: Plato v. Diogenes

In “Socrates, Cynics and Flat-Nailed, Featherless Bipeds,” Nickolas Pappas describes two competing philosophical types that arose from the example Socrates set: sober Academics like Plato and mangy Cynics like Diogenes. “Philosophy has pulled in both directions, systematic and subversive, for as long as it has remembered Socrates. … The Academy had the originality to envision an intellectual society … distinguished by the virtues of modesty and self-control, always ready to usher new students into the tradition. Philosophy as a tradition would have withered without an academy to live in. If it sometimes appears to be withering within the academy, that is because the subversive side of Socrates has its appeal: the virtues of the eccentric, above all eccentric courage, and the willingness to make your life an improvisation.”

Add your own egg

In “Bringing Philosophy to Life,” Nakul Krishna reflects on his introduction to philosophy by way of reading Bernard Williams. Along the way, there are many interesting points about ethics in general, utilitarianism in particular, other areas of philosophy, and what attracts people to philosophy at all. Williams brought “depth” to philosophy.

Williams never disdained rational argument, but he never thought it was enough by itself: “Analytic argument, the philosopher’s specialty, can certainly play a part in sharpening perception. But the aim is to sharpen perception, to make one more acutely and honestly aware of what one is saying, thinking and feeling.” Unhedged with cautious qualifications, his work goads you to distinguish what you actually think from what you think that you think. If his prose, compressed and epigrammatic, stands up to rereading today, as analytic philosophy seldom does, it’s because it leaves room for its readers to add something of themselves to it. A reader’s thought, Williams said, “cannot simply be dominated … his work in making something of this writing is also that of making something for himself.” For every reader comes to philosophy with “thoughts of his own, ways of understanding which will make something out of the writing different from anything the writer thought of putting into it. As it used to say on packets of cake mix, he will add his own egg.”

Having no reasons

In “How to Choose?,” Michael Schulson describes situations in which the rational thing to do might be to choose without having reasons for your choise. “When your reasons are worse than useless, sometimes the most rational choice is a random stab in the dark.”

Ought implies can … or not

In “The Data against Kant,” Vlad Chituc discusses psychological research challenging Kant’s principle that ought implies can. This is the principle that “it would be absurd to suggest that we should do what we couldn’t possibly do.” The research shows that there are common situations in which nonphilosophers do think it makes sense to say someone ought to do something that it is impossible for them to do it. In these situations “ought” has more to do with “blame” than with “can.” This in turn raises questions about “experimental philosophy” and the role the intuitions of nonphilosophers ought to play in philosophical analysis. Can we draw conclusions about what we ought to think from data about what some people actually think?

Free will and neuroscience

Which happens first … a conscious decision to do something or the brain activity associated with doing it? Thanks to experiments Benjamin Libet conducted in the 1980s, it seemed that “the timing of … conscious decisions was consistently preceded by several hundred milliseconds of background preparatory brain activity.” It seemed, that is, that our brains had already acted to carry out what we only later consciously decided to do. But in “Neuroscience and Free Will Are Rethinking Their Divorce,” Christian Jarrett says that may be changing. As researcher Dr. John-Dylan Haynes puts it, neuroscience may actually show that “a person’s decisions are not at the mercy of unconscious and early brain waves.”

Phantom attention

In “How Phantom Limbs Explain Consciousness,” Michael Graziano says that “the brain’s model of the body can tell us a lot about its model of attention.” Just as the brain generates a schema of the body, it generates a scheme of attention. “You know, the feely thing inside me. Consciousness.”