William Irvine explains and updates a Stoic formula for a happy, meaningful life. It has to do with the number of days you have left to live and the number of times you will do something in the remainder of your life. (Note that “Irvine” is misspelled in the title of this post on the “Stoicism Today” blog.)

Month: May 2015

Peter Singer on racism and speciesism

In an interview with George Yancy, Peter Singer discuss the origins and nature of racism and speciesism: “I don’t see any problem in opposing both racism and speciesism, indeed, to me the greater intellectual difficulty lies in trying to reject one form of prejudice and oppression while accepting and even practicing the other. And here we should again mention another of these deeply rooted, widespread forms of prejudice and oppression, sexism. If we think that simply being a member of the species Homo sapiens justifies us in giving more weight to the interests of members of our own species than we give to members of other species, what are we to say to the racists or sexists who make the same claim on behalf of their race or sex? … The more perceptive social critics recognize that these are all aspects of the same phenomenon. The African-American comedian Dick Gregory, who worked with Martin Luther King as a civil rights activist, has written that when he looks at circus animals, he thinks of slavery: “Animals in circuses represent the domination and oppression we have fought against for so long. They wear the same chains and shackles.”

Do chimpanzees have rights?

A New York state court heard arguments that chimpanzees can be considered persons with some legal rights. In connection with that case, the philosopher Peter Singer argues that there is no good reason to keep chimpanzees and apes in prison: “The ethical basis for extending basic rights to chimpanzees and the other nonhuman great apes is simple: chimpanzees are comparable to three-year-old humans in their capacity for self-awareness, for problem-solving, and in the richness and complexity of their emotional lives, so how can we assign rights to all children and not to them?” And if chimpanzees have any kind of rights, can chimpanzees who were research subjects in developing vaccines that save human lives be left to die on an island when no longer needed for research?

Does color exist?

Is color in your mind or in the thing? Is that dress white and gold or blue and black? Malcolm Harris’s review of a new work of philosophy about color can help you think about that. “In her new book Outside Color, University of Pittsburgh professor M. Chirimuuta gives a serendipitously timed history of the puzzle of color in philosophy. To read the book as a layman feels like being let in on a shocking secret: Neither scientists nor philosophers know for sure what color is.” It turns out color is not an object of sight but a way of seeing them.

Returning women to the history of philosophy

In “Reviving the Female Canon,” Susan Price notes: Despite their influence in early modern philosophy, “the era’s women thinkers are absent from historical anthologies of philosophical works. A group of scholars is trying to change that.” This may help with the larger problem of the under-representation of women in philosophy.

In the beginning

Cosmology attempts to understand the origin and structure of everything. Where is cosmology headed today? Ross Anderson asks: “Cosmology has been on a long, hot streak, racking up one imaginative and scientific triumph after another. Is it over?” From ancient Greece to the modern world, philosophy played a big part in developing conceptions of the cosmos. “To create a cosmos, a story that encompasses the origins and ultimate fate of all that is, you have to leave established science behind. You have to face down the cold void of the unknown. Philosophers are always in a dogfight to prove their utility to society, but this is something they do well.” And if the physicists working on cosmology today are facing a creative crisis, philosophical methods and distinctions may help. Indeed, Paul Steinhardt, the director of the Princeton Center for Theoretical Sciences, says, “I wish the philosophers would get involved.”

Self, with or without selfies

Stan Persky’s book review of Barry Dainton’s Self: Philosophy in Transit is an extended, entertaining, and instructive grand tour of many ideas about the self, that remarkable ability humans have “to sleepily glance at the bathroom mirror in the morning, and not only recognize ourselves, but also reflectively note, ‘Hmm, I don’t like myself very much these days. I wonder what I can do to change who and/or what I am.’” Thought experiments like the “ultimate simulation simulation machine” and “teleportation” make an appearance along the way.

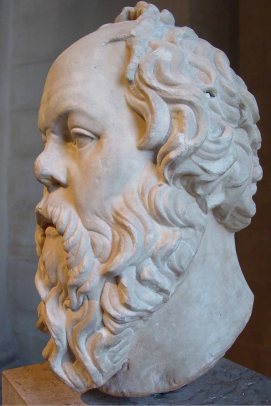

Cicero … and how to live

In “Cicero on Living a Stoic Life,” John Sellars explains Cicero’s view that there are four dimensions to who you are: common human nature, your own character traits, the circumstances in which you find yourself, and the career you choose. “So, how to live a Stoic life? The top priority remains a life in harmony with Nature/reason/virtue. Then there are the chance circumstances in which we find ourselves, out of our control and ultimately laid down by Nature too. But also central in Cicero’s account is the idea that we remain true to our own individual natures, to who we are. Thus self-knowledge becomes vital for a life in harmony with nature. Once we feel secure that we know who we are, what our strengths and weaknesses are, where we fit in the world, then the only decision to be made is how best to remain true to ourselves in the circumstances in which we find ourselves.” And all of this raises challenging questions about how much is up to you and how much just happens to you.

Are we awe-deprived?

We now use “awesome” to describe almost everything. But how often do we experience true awe, the goose bumps that come with that “feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends our understanding of the world.” Psychologists Paul Piff and Dacher Keltner say we are “awe-deprived.” And that may help explain why “people have become more individualistic, more self-focused, more materialistic and less connected to others.” Piff and Keltner “suggest that people insist on experiencing more everyday awe, to actively seek out what gives them goose bumps, be it in looking at trees, night skies, patterns of wind on water or the quotidian nobility of others — the teenage punk who gives up his seat on public transportation, the young child who explores the world in a state of wonder, the person who presses on against all odds.”

When medical treatment is futile

Futility cases … when doctors believe further medical treatment is futile and yet the patient’s family asks for treatment beyond palliative care … are nerve-wracking: “For most doctors, these cases present a crisis of conscience. How can we obey a central pillar of our profession — to do no harm — when we are forced to provide treatment that will only prolong suffering?” In “It’s Not Just about the ‘Quality of Life,’ ” Sandeep Jauhar sugguests: “Embracing the ethic of social justice can help us out of this morass. Social justice in medicine promotes the allocation of limited resources to maximize societal benefit.”