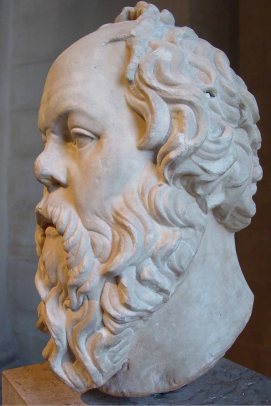

In “Whom Does Philosophy Speak For,” Seyla Benhabib and George Yancy consider that sometimes philosophy speaks for and about everyone and yet at other times seems not to. Unfortunately, “a dynamic of freedom for some and domination for others is present in much of Western philosophy.” This has a significant bearing on our understanding of democracy. Benhabib says, “Western philosophy, as distinguished from myth, literature, drama and many other forms of human expression, speaks in the name of the universal. Philosophy emerges when Socrates and Plato show how we have to free ourselves from the ‘idols of the city,’ and when the pre-Socratics ask about what constitutes matter and the universe, rejecting the answers provided by the Greek polytheistic myths.” And yet she also agrees when Yancy points out “that within the Western philosophical tradition, the mind, coded as white and male, is privileged over the body, coded as female or a signification of blackness, creating a false, disembodied practice.”

Locke

Thought experiments

In “5 Thought Experiments That Will Melt Your Brain,” Evan Dashevsky says that because “some science is too big, dangerous, or weird to happen in the lab,” thought experiments “may be the most valuable experiments of all.” But notice that all five of his examples are from philosophers.

Are you a story?

Some philosophers and others claim that the best way to understand self-identity is to think of it as a story you work on and tell yourself as you live. It’s that story that gives your life focus, meaning, and purpose. But in “I Am Not a Story,” Galen Strawson disagrees: he thinks the idea that life is a story is false and even dangerous.

Painful memories

In “A Good Forgetting,” Marianne Janack considers whether we may be happier forgetting some things despite the close link between memory and personal identity. “Personal identity is tied to memory, but sometimes we find peace, clarity and a true sense of completeness in the lapses.” What if we stripped away the pain so that we kept the memory but without its emotional baggage?

Does color exist?

Is color in your mind or in the thing? Is that dress white and gold or blue and black? Malcolm Harris’s review of a new work of philosophy about color can help you think about that. “In her new book Outside Color, University of Pittsburgh professor M. Chirimuuta gives a serendipitously timed history of the puzzle of color in philosophy. To read the book as a layman feels like being let in on a shocking secret: Neither scientists nor philosophers know for sure what color is.” It turns out color is not an object of sight but a way of seeing them.

Self, with or without selfies

Stan Persky’s book review of Barry Dainton’s Self: Philosophy in Transit is an extended, entertaining, and instructive grand tour of many ideas about the self, that remarkable ability humans have “to sleepily glance at the bathroom mirror in the morning, and not only recognize ourselves, but also reflectively note, ‘Hmm, I don’t like myself very much these days. I wonder what I can do to change who and/or what I am.’” Thought experiments like the “ultimate simulation simulation machine” and “teleportation” make an appearance along the way.

The disremembered

In “The Disremembered” Charles Leadbeater claims that “[p]hilosophy is not of much practical use with most illnesses but in the case of dementia it provides insights about selfhood and identity that can help us make sense of the condition and our own reactions to it.” There are two broad philosophical explanations of self-identity. There is the mind-based or memory-based explanation of Descartes and Locke. But when mind and memory fade, so does self-identity. But there is another philosophical tradition that can help: “philosophers in this tradition contend that who we are depends not simply on our self-reflective ability to marshal our memories but, crucially, on our relationships with other people and how we are embedded in the world around us.” In other words, beware of being a memory snob.

Moral character: it’s who you are

Nina Strohminger explains why your moral character is the key to your self-identity. “‘Know thyself’ is a flimsy bargain-basement platitude, endlessly recycled but maddeningly empty. It skates the very existential question it pretends to address, the question that obsesses us: what is it to know oneself? The lesson of the identity detector is this: when we dig deep, beneath our memory traces and career ambitions and favourite authors and small talk, we find a constellation of moral capacities. This is what we should cultivate and burnish, if we want people to know who we really are.”

Locke, Leibniz, and the blind boy who now sees

Quaere, how much do we really see? What can we learn about knowledge when sight is restored to a 13-year-old boy who had been blind since birth? Charlie Huenemann explains what the empiricist Locke and the rationalist Leibniz had to say about this. And don’t miss the very interesting readers’ comments to this very interesting essay.

Alzheimer’s, memory, morality, and self-identity

Alzheimer’s challenges our understanding of memory and self-identity. There is reason to think your moral beliefs and practices may define your “true self” more than your memory.