In “Unnatural Laws,” Nancy Cartwright challenges the idea that everything could ultimately be accounted for with universal laws of nature that are immutable and without exceptions. “We live our everyday lives in a dappled world unlike the world of fundamental particles regimented into kinds, each just like the one beside it, mindlessly marching exactly as has forever been destined. In the everyday world the future is open, little is certain, the unexpected intrudes into the best-laid plans, everything is different from everything else, things change and develop, and different systems built in different ways give rise to different patterns. For centuries this everyday world was at odds with the scientific world governed through-and-through by immutable law. But many of the ways we do science today bring the scientific image into greater harmony with what we see every day: much of modern science understands and manipulates the world without resort to universal laws.’

science

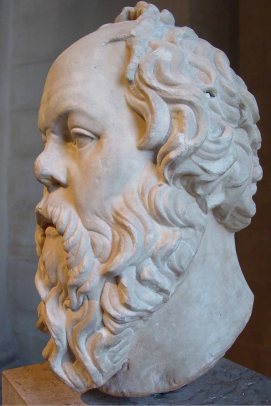

More about how Aristotle invented science

Another review, this one by Henry Gee, of Armand Marie Leroi’s The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. It’s true that Aristotle make some mistakes in his investiations. But “in science, there is no shame in being wrong. Scientists are wrong all the time. Aristotle was a pioneer in that he started not with a prior scheme, but sought, as dispassionately as he could, to explain what he saw.”

How Aristotle invented science

Susan H. Gordon’s review of Armand Marie Leroi’s The Lagoon: “And so, in 2014, Aristotle joins the ranks of his fellow biologists. ‘Intimacy with the natural world shines from his works,’ writes Leroi, a communion that allowed Aristotle to ‘sieve the ocean of natural history folklore and travelogue for grains of truth from which to build a new science.’ Following his new scientific inquiry, Aristotle arrived at a final why: Why does any of this happen at all? It would take centuries before Darwin could find a scientifically plausible answer, and in ancient Greece Aristotle looked again to the practical for his own: Biological systems are true so that we might exist. And to exist is simply better than to not exist.”

Embracing the unexplained …

… by putting the immaterial on the table? Is there any kind of thing in the universe in addition to the stuff physicists study?

In “Visions of the Impossible,” Jeffrey Kripal says: “After all, consciousness is the fundamental ground of all that we know or ever will know. It is the ground of all of the sciences, all of the arts, all of the social sciences, all of the humanities, indeed all human knowledge and experience. Moreover, as far as we can tell, this presence is sui generis. It is its own thing. We know of nothing else like it in the universe, and anything we might know later we will know only through this same consciousness. Many want to claim the exact opposite, that consciousness is not its own thing, is reducible to warm, wet tissue and brainhood. But no one has come close to showing how that might work. Probably because it doesn’t.” Under the circumstances, Kripal says, we need an account of consciousness that synthesizes the “Aristotelian” materialist understanding of consciousness with the “Platonic” nonmaterialist understanding.

In “Science Is Being Bashed by Academics Who Should Know Better,” Jerry Coyne replies: “When science manages to find reliable evidence for … clairvoyance, I’ll begin to pay attention. Until then, the idea of our brain as a supernatural radio seems like a kind of twentieth-century alchemy—the resort of those whose will to believe outstrips their respect for the facts.”

And in turn Kripal replies to Coyne in “Embracing the Unexplained, Part 2,” that Coyne’s piece is “name-calling and an attempt to control and manipulate the data so that the ‘proper’ conclusions are reached. My point is a simple one: If you put the ‘impossible’ data on the table, you will arrive at different conclusions.” And to make his case he calls on Barbara Ehrenreich’s “A Rationalist’s Mystical Moment” for support.

Is philosophy obsolete?

How philosophy makes progress. Philosophy isn’t literature, and it is isn’t failed or primitive science. Instead, according to Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, its task is to make our points of view increasingly coherent. “It’s in terms of our increased coherence that the measure of progress has to be taken, not in terms suitable for evaluating science or literature. We lead conceptually compartmentalized lives, our points of view balkanized so that we can live happily with our internal tensions and contradictions, many of the borders fortified by unexamined presumptions. It’s the job of philosophy to undermine that happiness, and it’s been at it ever since the Athenians showed their gratitude to Socrates for services rendered by offering him a cupful of hemlock.”

What scientific idea is ready for retirement?

Edge.org’s big question for 2014. 175 short essays by some of today’s best known thinkers. “Science advances by discovering new things and developing new ideas. Few truly new ideas are developed without abandoning old ones first. As theoretical physicist Max Planck (1858-1947) noted, ‘A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.’ In other words, science advances by a series of funerals. Why wait that long?”

Science … philosophy’s friend or foe?

Are the humanities (including especially philosophy) and science two separate and independent methods that deal with two separate and independent realms? Or should they be integrated with each contributing to the other? Or, as Arts & Letters Daily summarized the discussion: “An academic turf and budget battle is under way between science and the humanities. Are you for porous borders or a two-state solution?” Is science the single best way to figure out what reality is and how we ought to live our lives, or is it philosophy’s task to tell science what its limits are? This is “round three” of a discussion initiated by Steven Pinker and then picked up by Leon Wieseltier. The “round three” exchange includes links to the first two rounds. And here is Daniel Dennett’s comment on the debate.